The tale of the Collared Earthstars

How many hundreds of times did Claude Monet paint lilies? The great impressionist must have seen their flowering forms in his sleep, and first thing when he woke in the morning. The way to learn what things are and how they live is undoubtably through repeated observation. But there is also a line between a rational pursuit of knowledge and an obsession. At what point is that line crossed? When does repetition compulsion set in? When does obsessive compulsive disorder take hold?

Not that I wish to compare our humble efforts to those of an artistic genius. But the fact remains that lichens have taken up an increasing amount of time in recent months. That said, I'm always pleasantly surprised how familiar places can consistently yield new treasures. And you can also glean a wealth of new details from things seen before.

Peltigera membranacea

We were back in the cemetery outside Kingswear, tying up some loose ends. We have seen this lichen species before during our visits but the camera has always seemed allergic to capturing it. Sherry was determined to nail it this time. As well as the varying shapes and sizes of the thallus, Peltigeras can be distinguished by examining the spines underneath (known as rhizines).

Cladonia chlorophaea

There always seems to be one in the ranks that comes out blurred. It could be the equivalent of the school photo, where everyone stands assembled and dutifully still - barring the one boy who moves or pulls a face. In reality there's probably a fault with the camera's auto-focus system. But on this occasion the squammules at the base are richer and clearer.

A Celtic cross tombstone

There are layers of lichens here, overgrowing each other. Though on rocks they are slower-growing than on trees (and probably harder to date) there must be a constant state of flux over fractions of millimetres.

A different Cladonia?

Sherry took an overhead shot of these in the gravel. They were in a place we had not previously thought to check: in a bed of gravel by a grave. These could be examples of Cladonia pocillum. Below the cups the squammules were arranged in erect rosettes, while the inside of some of the cups was extremely granular.

Close-up of Flavoparmelia caperata [mature specimen]

Although we have recorded this species fairly frequently, this specimen has a decent display of coarse, granular soredia.

Flavoparmelia caperata

And this was what it looked like from a distance. This is an older specimen because part of the middle has fallen out.

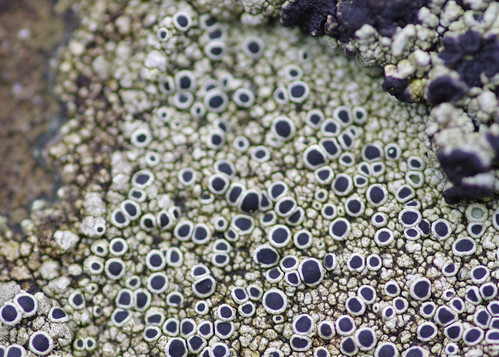

Lecanora gangaleoides

I recently purchased a Field Studies Council laminated, fold-out guide on churchyard lichens. It is proving very handy indeed. Instead of carrying the book, and wading hopelessly through it, a few species have been immediately to hand.

Possibly Trapelia involuta

We were starting to wonder if this might be the outing when we could confirm everything we saw. But a run of perplexing finds soon knocked our confidence down a peg or two. The image above looked similar to Trapelia involuta but I wasn't convinced it was similar enough. For one thing, the discs are darker here. And there seem to be more of them.

Sherry went from right to left along the same tombstone. You can see a couple of apothecia of the previous species to the extreme right. Only now the thallus has been overrun with brown discs. While being roughly the same colour (albeit a bit darker) these are flatter and have almost a wavy, rather then a nobbly appearance. I can only conclude that they belong to a different species.

Further left still along the rock, this image was cropped thin and wide to accentuate how crowded the surface was with discs.

Verrucaria macrostoma?

A different tombstone. The colour is a touch lighter, the texture about right. Acarospora fuscata is a similar species and this requires further investigation.

Here, the crust is lumpy and cracked. A red spider mite has strayed into the picture. Sometimes you can have more success photographing insects by pointing the camera at a random area and pushing the shutter. If only this one had wanted to steal the limelight a bit more and take centre stage!

This species was like the King Alfred's Cakes of the lichen world.

Caloplaca crenularia

These tiny discs proved a direct match and put us back on the road to success.

Cladonia flavescens

We've been looking for a 'textbook' example of this species during our last few outings. This one ticked all the boxes and the clarity of the lobes was impressive.

Alexanders (Smyrnium olusatrum)

This species was reputedly brought to these shores by the Romans. It was used as a pot herb (it tastes similar to celery) and is common in areas close to the sea. It is also a member of the umbellifer family which has deadly poisonous members. If you are inclined to forage for wild food please don't take the risk unless you are 100% certain what something is.

At this point we left the cemetery behind and headed across the road and into Hoodown. We took the path ahead and followed it straight through under the trees. Just before the bend, we turned off left, going down a narrow path with some steps and house walls on our right hand side. There was an area of rough ground on our left. Just beyond the path we found these on an oak sapling.

Oak Marble Galls (Andricus kollari)

At the bottom of the steps, we turned left past Mexican fleabanes waving their daisy heads in the breeze. Although we've been to Hoodown many times in the last few months, one path remained to be explored. It was an ordinary-looking track and I didn't think there was much to warrant a closer look but Sherry insisted we try our luck. I'm certainly glad we did. We had not gone too far when I spotted these in the exposed hedgebank.

Collared Earthstar (Geastrum triplex)

Apparently these are the commonest species of Earthstar in the U.K. Hitherto, we must have always been looking in the wrong places (or at the wrong times). There were a handful of specimens in the mossy soil, in close proximity to one another. Most were like the one above, possessing two holes at the top. But we did see one with one hole. I wonder if this is an earlier stage of growth.

This is its spent fruiting body

This is a much later stage of development. The fungi has released its spores and has now taken on a dramatically altered appearance. Before finding the answer I needed in the field guide I would never have guessed that these two belonged to the same species.

Jelly Ear (Auricularia auricula-judae)

Part of the hedgerow had been cleared out. On the remains of what had been an elder tree, we found another Jelly Ear. This was a far more typical example of the species than those we found at Lupton the previous week.

Alexanders Rust (Puccinia smyrnii)

Rusts attack a range of plants and flowers including roses, brambles and meadowsweet. I wonder if rusts have always been around to attack plants or if certain species have naturally evolved or mutated over time. And are there any plants that have been able to develop their own defence mechanisms against this onslaught?

Candelariella reflexa

This fluffy yellow lichen almost has a candy floss texture from a distance. Here, it is overgrowing a crustose species of lichen.

Physcia aipolia

We found this unmistakeable species on the railing of a fence. It puts me in mind of a many-headed, multi-eyed, mutating monster you might find in the pages of a sci-fi comic book.

Stinking Hellebore (Helleborus foetidus)

By the side of the path, our good fortune continued. This species is one of the first flowering plants to emerge every year. It is said to exude an unpleasant odour but we didn't poke our noses close enough to notice any untoward scent.

We had come to the end of the track and turned off right down another set of steep steps towards the creek. The tide was out. On the rocks, another species demanded to be added to the list.

Xanthoria parietina can grow just about anywhere, even in polluted areas.

And finally - a cabbage!

This could be a common garden variety or one of its wild variants. They must like the sea air because I have seen a number of these around Kingswear and Dartmouth. They are to be found, scattered here and there, on both sides of the river and the coast path beyond.

Comments

Add a Comment